Owls in Western Democratic Republic of the Congo

During 20 August to 15 September 2004, I engaged in an expedition to the Congo River Basin in western Democratic Republic of the Congo. I explored a number of remote forests and stayed in 8 different Bantu and Pygmy villages south of the city of Mbandaka down to Lac Ntumba (Lake Tumba) and up the Ubange and Congo Rivers and some of their tributaries, including Lombobo River, Monioto Channel, Irebu Channel (0° 6.7' to 1° 5.4' S latitude, 17° 45.0' to 18° 16.4' E longitude).

The purpose of the expedition was to assist with community-based forest planning. As part of this objective, I sought owls in a variety of forest and vegetation conditions to determine which owl species may be present in more and less disturbed situations. To aid identification and to solicit responses, I carried a cassette tape with Central African owl sounds from a commercially-available CD set (Chappuis 2000). I also compared observations with the often-scant descriptions of owl vocalizations given in Barrow and Demey (2001), König et al. (1999), and van Perlo (2002).

In total, I encountered 11 owls among 3 species: 1 Red-chested Owlet (Glaucidium tephronotum), 8 African Wood Owls (Strix woodfordii), and 2 probable Pel's Fishing Owls (Scotopelia peli).

The following table summarizes my encounters.

| Date | Location (village) | Owls | Situation |

| 8/26,28 | Bogonde Drapeau | Red-chested Owlet (1) | secondary forest adjacent to village; heard only |

| 8/27 | Bogonde Drapeau | Pel's Fishing Owl (1) | older secondary swamp forest adjacent to village; heard only |

| 8/28-29 | Kalamba-Biambo | African Wood Owl (6) | dense old secondary terre firme forest outside village; heard, taped, spotlighted |

| 9/1 | Iyembe Monene | African Wood Owl (1) | in village using taller trees as roost, spotlighted |

| 9/5 | Botuali | African Wood Owl (1) | in village among tall trees, spotlighted |

| 9/7 | Bobangi | Pel's Fishing Owl (1) | taller secondary wet forest behind village, heard only |

Vocalizations of African Wood Owls in the Congo

I also taped songs and calls of African Wood Owls outside the village of Kalamba-Biambo and am analyzing the sounds by comparing to songs and calls of this species recorded in Kenya, Zimbabwe, and elsewhere.

My initial findings are that the songs of this species in the Congo differ significantly from its songs elsewhere in three ways:

- the initial two notes are far less prominent and are often condensed into a single note,

- the song is shorter in duration, lasting on average about 1.2 seconds as compared to about 1.7 seconds elsewhere, and

- the entire song is given on a far narrower range of frequencies, that is, it lacks the 'bouncy ball' effect prevalent in songs of this species elsewhere, including where I have heard it in Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and South Africa, and as compared to the recording of this species in Kenya on the CD (Chappuis 2000).

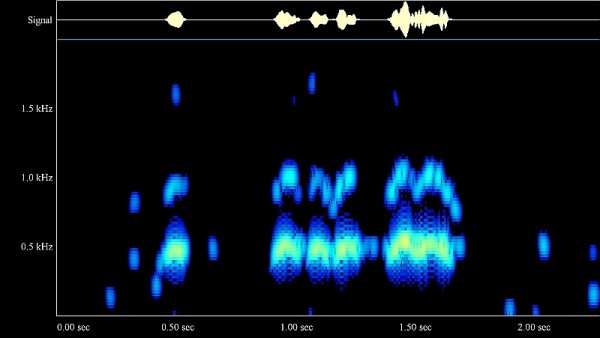

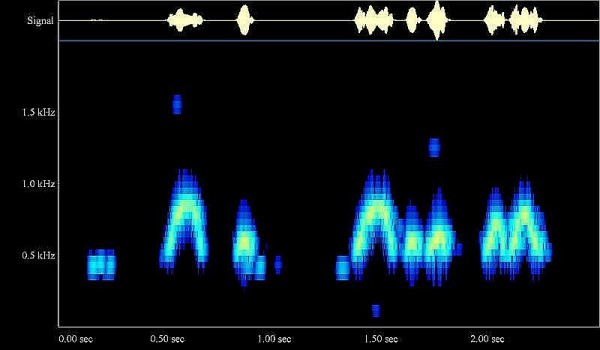

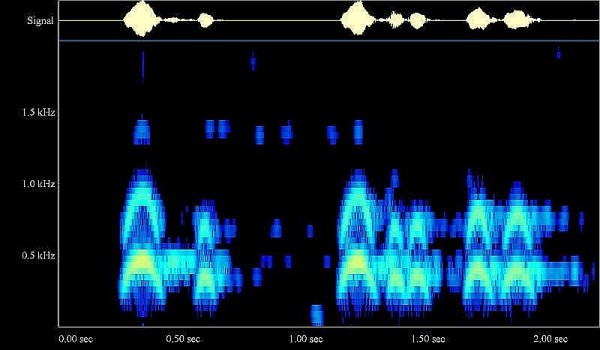

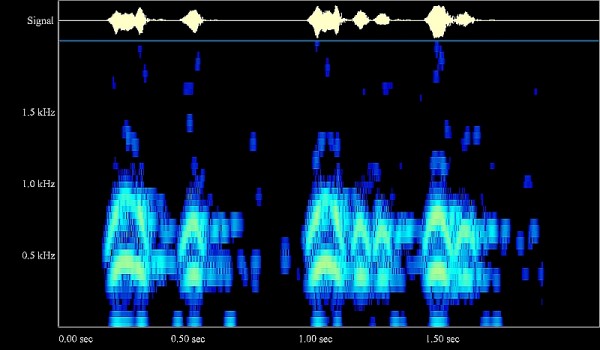

These differences are noticeable on the following sound spectrograms of African Wood Owl songs in three geographic areas. These plots show a duration of about 2 seconds on the x axis and a frequency range up to about 2 kHz on the y axis.

The first is an African Wood Owl song I taped in the Congo. This is likely a male, as males may have deeper voices than do females (Delport et al. 2002):

1. African Wood Owl song in western Democratic Republic of the Congo

The second is an African Wood Owl song I taped in Victoria National Park in northwestern Zimbabwe (this may be a female, which generally sings at a higher pitch than males, but still note the greater range of frequencies of the main notes of the song):

2. African Wood Owl song in northwestern Zimbabwe

Also, commercially available sound files of African Wood Owl songs from Kenya (Chappuis 2000) and South Africa (Gibbon 1995) are quite similar to the Zimbabwe call shown above. For example, here is an African Wood Owl song recorded in Kenya (probably a male):

3. African Wood Owl song in Kenya

And here is an African Wood Owl song recorded in South Africa (again, probably a male):

4. African Wood Owl song in South Africa

Whether these differences I discovered signal a unique taxonomic entity or just local individual variation of this species has yet to be determined.

Many thanks to my hosts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo for getting me to the remote locations, particularly to Michael Brown and his staff of Innovative Resources Management. My thanks also to the many local villagers who risked the numerous army ant raids in the dark night forests to show me forest trails and some of the owl locations.