Owl encounters

Just imagine. You decide to take a birding tour to an exotic island. You sign up, make the flight arrangements and even arrive 2 days early. After settling in, you search for an English newspaper and find one in the lobby. On page one is a photograph of an owl. A bit unusual, perhaps, but then the article proclaims it to be a new species just discovered by the local ornithologist that will be with you on the tour. Can this be possible? Are you dreaming? This just doesn't happen.

But it did to me. In February (2001) I was in Sri Lanka, an island country sometimes called the teardrop of India. I was scheduled to start the official birding tour in 2 days with Sunbird, a British bird tour company, but the day before the tour was to begin I had planned to spend a day birding in the Colombo area with Upali Ekanayaka and David Fisher. Upali is one of the 2 leading field ornithologists in Sri Lanka and David is a principal of Sunbird, but was not leading the tour. David enjoys his work so much he was on a busman s holiday and was a tour participant.

David was greatly exited when I showed him the newspaper the next day and, of course, we discussed this new owl with Upali while we were out birding. Upali had not yet seen the bird, but said that he and Deepal Warakagoda had been hearing it in the jungle for about 5 years. Deepal, the pre-eminent field ornithologist in Sri Lanka, and Upali were the best of friends and it was Deepal that was leading our Sunbird tour along with Steve Rooke of England.

With Upali that day we visited the Bellanwilla-Awtidiya marshes and saw spot-billed pelicans, Indian pond herons, a yellow bittern, a black bittern, Brahminy kites, pheasant-tailed jacanas, rose-ringed parakeets, white-throated kingfishers, black-hooded orioles, brown shrikes, rose-colored starlings, red-vented bulbuls, zitting cisticolas, plain prinias, a Blyth s reed warbler, black-headed munias, and a long-billed sunbird. Mostly new birds for me and even a few for David. But dominating our thoughts and conversation that day was the owl. Was there a chance we might actually see it? What could Upali tell us? He was somewhat chagrined that he hadn't seen it; from what Deepal had told him, it was a scops owl, probably of the genus Otus. (Scops owls are very small owls and there are some 44 species found throughout the world. They are closely related to the screech owls found in the Americas). But he couldn t tell us much more and it was apparent we had to wait until the rest of the group arrived and Deepal joined us.

The next day everyone arrived for the tour. Cecil, from Louisiana, had seen almost 5,000 species and was eager to add to his list. He hoped to hit 5,000 on a trip to Ethiopia in the fall. Gavin and Margaret from Scotland were Sunbird veterans. Stephen, a keen birder, worked for the British Ministry of Agriculture and Richard was a banking computer specialist. The leader, Steve Rooke, had led tours to Sri Lanka for 10 years and, as he had decided this was to be his last trip, his wife joined him.

When David and I showed Steve the newspaper article he was stunned. He was an expert on the birds of Sri Lanka and knew how rare it was to actually discover a new species anywhere. Noted author and bird guide Ben King had rediscovered an owl in India the year before. It had not been seen for over 100 years and had been thought to be extinct. But to find a distinct new species was truly amazing. This was exciting news for the birding world. All we could do now was wait for Deepal.

When he arrived later, we found him to be an affable Sri Lankan with an excellent command of English. Though only 35, the slender and soft-spoken guide had been actively birding since the age of 10 and had been a full time field ornithologist and guide in Sri Lanka for 10 years. Although a humble person, Deepal was enjoying his new notoriety on the island for having discovered a new species.

He had first heard the owl in the jungle of the Sri Lankan wet zone in February, 1995.It was a call he hadn't heard elsewhere and it baffled him. He had made a tape of the sound but it was not of good quality and when he played it back the owl was either too far away to hear it or wouldn t respond. In March, 1996, he was able to make a better recording of the sound, but although he continued to try it, off and on, for several years he had no success in attracting the bird so he could actually see it.

Then on January 23, 2001, he had his first sighting. He was guiding a client through the jungle in the night and he heard the owl much closer than usual. He played the tape and in it flew. He could actually see it as he flashed a light up in the tree and knew immediately he was looking at a new species of scops owl. Unlike the other two scops owl species found on the island, this one had no ear tufts and was less marked. It had a rufous crown and was whitish on the belly.

He knew he had to document his find in order to achieve acceptance from the birding community. He returned to the area another night with a professional photographer, the Chairman of the Ceylon Bird Club and another club member. Once again the bird responded to his tape and flew in. It was 8:00 pm and very dark but they could see it well with a flashlight. All agreed that this was a sensational new find and the photographer was able to get a suitable picture.

Now it was February 25th and he had a group of birders to lead for 2 weeks of birding around Sri Lanka. Could he possibly show it to us? Would he? He made it clear from the outset that he planned to keep the location of the owl a secret until he had a chance to fully study it. However, as a special favour to Steve Rooke, whom he had known for 10 years, he would make an effort to relocate the owl one night provided everyone agreed not to disclose its location. We all agreed, of course. This was just too exciting to pass up!

Thus, one night in February, in the Sri Lankan Wet Zone Rain Forest, we set out. First crossing a river by dugout canoe, then hiking on a trail through the jungle. Our stated goal was to see the endemic Ceylon frogmouth, now called Sri Lanka frogmouth, but we were also keenly aware that this was our one chance to see the owl. We got to a point on the trail where the frogmouth had previously been seen, but what was that? Deepal heard in the distance the call of the owl. But it was too far away, he said, and wouldn t respond to his tape. Well, at least we heard it.

We turned our attention to the frogmouth. Steve played the tape for the frogmouth. We waited. Nothing happened! We heard only the various jungle noises and howls that one hears in movies, and began to wonder what snakes do at night. Then, voila!, 2 frogmouths flew into the tree above us. With the aid of a light we could see this strange bird, somewhat of a cross between an owl and a nightjar, with a huge mouth for catching moths and insects on the wing at night.

As we started to make our way back through the night, Deepal stayed behind so he could hear the night sounds better. He soon came hurriedly up to us saying: I hear it, and it s much closer now. Come with me. We made our way through the forest to a spot where we could hear two owls calling to each other. One seemed near. Deepal played the tape he had made of it. It silently flew in and he flashed his light on it. There it was! Looking back at us! Just as Deepal had described it. A little guy, maybe 8 inches tall and reddish brown, with no apparent ear tufts and whitish on the lower belly. Very different from the Oriental Scops Owl and Indian Scops Owl also found on the island. The magic moment was broken when the owl flew away and we knew it was best at that point to leave it alone, presumably to find its mate and go hunting.

Scops Owl photo © Chandima Kahandawala

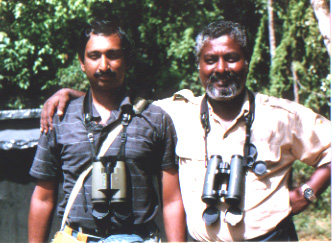

Deepal Warakagoda & Upali Ekanayaka

Footnote: Since this article was written, the Owl has been classified as the Serendib Scops Owl Otus thilohoffmanni.